Jean-Louis Le Loutre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre (; 26 September 1709 – 30 September 1772) was a

The conquest of Acadia by Great Britain began with the 1710 capture of the provincial capital, Port Royal. In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, France formally ceded Acadia to Britain. However, there was disagreement about the provincial boundaries, and some Acadians also resisted British rule. With renewed war imminent in 1744, the leaders of New France formulated plans to retake what the British called Nova Scotia with an assault on the capital, which the British had renamed Annapolis Royal.

The conquest of Acadia by Great Britain began with the 1710 capture of the provincial capital, Port Royal. In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, France formally ceded Acadia to Britain. However, there was disagreement about the provincial boundaries, and some Acadians also resisted British rule. With renewed war imminent in 1744, the leaders of New France formulated plans to retake what the British called Nova Scotia with an assault on the capital, which the British had renamed Annapolis Royal.

As an official peace existed between France and Britain, Le Loutre led the guerrilla resistance to the British building forts in the Acadian villages, because the French army was unable to fight the British, who possessed the territory. Le Loutre and the French were established at Beauséjour, just opposite Beaubassin. Charles Lawrence first tried to establish control over Beauséjour and then at Beaubassin early in 1750, but his forces were repelled by Le Loutre, the Mi'kmaq, and Acadians. On 23 April, Lawrence was unsuccessful in setting a base at Chignecto because Le Loutre burned the village of Beaubassin, preventing Lawrence from using its supplies to establish a fort.

Defeated at Beaubassin, Lawrence went to Piziquid where he built Fort Edward; he forced the Acadians to destroy their church and replaced it with the British fort. Lawrence eventually returned to the area of Beaubassin to build

As an official peace existed between France and Britain, Le Loutre led the guerrilla resistance to the British building forts in the Acadian villages, because the French army was unable to fight the British, who possessed the territory. Le Loutre and the French were established at Beauséjour, just opposite Beaubassin. Charles Lawrence first tried to establish control over Beauséjour and then at Beaubassin early in 1750, but his forces were repelled by Le Loutre, the Mi'kmaq, and Acadians. On 23 April, Lawrence was unsuccessful in setting a base at Chignecto because Le Loutre burned the village of Beaubassin, preventing Lawrence from using its supplies to establish a fort.

Defeated at Beaubassin, Lawrence went to Piziquid where he built Fort Edward; he forced the Acadians to destroy their church and replaced it with the British fort. Lawrence eventually returned to the area of Beaubassin to build

In 1754 Bishop

In 1754 Bishop

Aware of his risk, Le Loutre escaped to Quebec through the woods. In the late summer, he returned to Louisbourg and sailed for France. His ship was seized by the British in September 1755, and Le Loutre was taken prisoner. After three months in

Aware of his risk, Le Loutre escaped to Quebec through the woods. In the late summer, he returned to Louisbourg and sailed for France. His ship was seized by the British in September 1755, and Le Loutre was taken prisoner. After three months in

Video - Abbe Le Loutre

BluPete

Daniel Paul Website, Mi'kmaq Account {{DEFAULTSORT:Le Loutre, Jean-Louis 1709 births 1772 deaths 18th-century French military personnel 18th-century French Roman Catholic priests Canadian military personnel from Nova Scotia Military history of New England Military history of the Thirteen Colonies Canadian military personnel from New Brunswick Acadian people Military history of Nova Scotia Canadian Christian religious leaders Military history of Acadia People from Morlaix Sipekneꞌkatik First Nation People of Father Le Loutre's War

Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the Holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in layman's terms ''priest'' refers only ...

and missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

for the Paris Foreign Missions Society

The Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (french: Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris, short M.E.P.) is a Roman Catholic missionary organization. It is not a religious institute, but an organization of secular priests and lay persons ...

. Le Loutre became the leader of the French forces and the Acadian

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the de ...

and Mi'kmaq militia

The military history of the Mi'kmaq consisted primarily of Mi'kmaq warriors (''smáknisk'') who participated in wars against the English (the British after 1707) independently as well as in coordination with the Acadian militia and French royal ...

s during King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

and Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Briti ...

in the eighteenth-century struggle for power between the French, Acadians

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the des ...

, and Miꞌkmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the nort ...

against the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

over Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

(present-day Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

and New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

).

Historical context

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

had been under the rule of the British since the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne o ...

in 1713. The British were settled mostly in the capital Annapolis Royal

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the n ...

, while Acadians and the native Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the northe ...

occupied the rest of the region. Île-Royale (present-day Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

) remained under French control, as it had been granted to the French under the Treaty of Utrecht, and the mainland portion of Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

and New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

) was British and contested by the French.

In 1738, the French had no formal military presence at mainland Nova Scotia because they had been evicted in 1713. The Acadians had refused to sign a loyalty oath to the British Crown since the defeat in Port-Royal Port Royal is the former capital city of Jamaica.

Port Royal or Port Royale may also refer to:

Institutions

* Port-Royal-des-Champs, an abbey near Paris, France, which spawned influential schools and writers of the 17th century

** Port-Royal A ...

in 1710, but the settlers were unable to assist French efforts to recapture Nova Scotia without French military support.

Life

Le Loutre was born in 1709 to Jean-Maurice Le Loutre Després, a paper maker, and Catherine Huet, the daughter of a paper maker, in the parish of Saint-Matthieu inMorlaix

Morlaix (; br, Montroulez) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in northwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

Leisure and tourism

The old quarter of the town has winding streets of cobbled stones and overhan ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

. In 1730, the young Le Loutre entered the ''Séminaire du Saint-Esprit'' in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

; both his parents had already died. After completing his training, Le Loutre transferred to the ''Séminaire des Missions Étrangères

The Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (french: Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris, short M.E.P.) is a Roman Catholic missionary organization. It is not a religious institute, but an organization of secular priests and lay persons ...

'' (Seminary of Foreign Missions) in March 1737, as he intended to serve the church abroad. Most of the priests associated with the Paris Foreign Missions Society

The Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (french: Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris, short M.E.P.) is a Roman Catholic missionary organization. It is not a religious institute, but an organization of secular priests and lay persons ...

were assigned as missionaries to Asia, particularly during the nineteenth century, but Le Loutre was assigned to eastern Canada and the Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the northe ...

, an Algonquian-speaking people. Le Loutre arrived at mainland Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

in 1738.

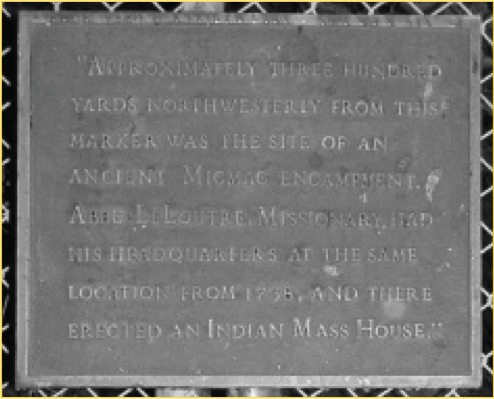

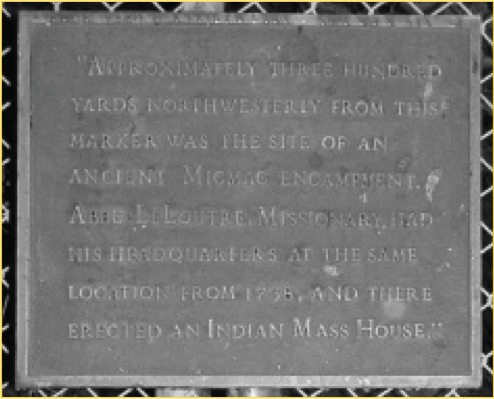

Île Royale

Shortly after being ordained, Le Loutre sailed forAcadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

and arrived in Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour, ...

, Île-Royale, New France in the autumn of 1737. He spent about a year at ''Malagawatch,'' Île-Royale, working with missionary Pierre Maillard

Abbé Pierre Antoine Simon Maillard (c. 1710 – 12 August 1762) was a French-born Priesthood (Catholic Church), Roman Catholic priest. He is noted for his contributions to the creation of a Mikmaq hieroglyphic writing, writing system for the Mi'k ...

to learn the Miꞌkmaq language

The Miꞌkmaq language (), or , is an Eastern Algonquian language spoken by nearly 11,000 Miꞌkmaq in Canada and the United States; the total ethnic Miꞌkmaq population is roughly 20,000. The native name of the language is , or (in some diale ...

. Le Loutre was assigned to replace Abbé de Saint-Vincent, at the Mission Sainte-Anne in ''Shubenacadie''. He left for Saint-Anne's on 22 September 1738. His duties included the French posts at Cobequid

The old name Cobequid was derived from the Mi'kmaq word "Wagobagitk" meaning "the bay runs far up", in reference to the area surrounding the easternmost inlet of the Minas Basin, a body of water called Cobequid Bay.

Cobequid was granted in 1689 to ...

and Tatamagouche

Tatamagouche (Mi'kmaq: ''Taqamiju’jk'') is a village in Colchester County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Tatamagouche is situated on the Northumberland Strait 50 kilometres north of Truro and 50 kilometres west of Pictou. The village is located along ...

. Lawrence Armstrong

Lawrence Armstrong (1664 – 6 December 1739) was a lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia and acted as a replacement for the governor, Richard Philipps, during his long absences from the colony.

Armstrong was born in 1664 in Ireland. According ...

was lieutenant-governor at Annapolis Royal

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the n ...

. Although Armstrong was initially annoyed that La Loutre hadn't presented himself at Annapolis Royale, on the whole, La Loutre's relations with the British authorities remained cordial.

King George's War

The conquest of Acadia by Great Britain began with the 1710 capture of the provincial capital, Port Royal. In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, France formally ceded Acadia to Britain. However, there was disagreement about the provincial boundaries, and some Acadians also resisted British rule. With renewed war imminent in 1744, the leaders of New France formulated plans to retake what the British called Nova Scotia with an assault on the capital, which the British had renamed Annapolis Royal.

The conquest of Acadia by Great Britain began with the 1710 capture of the provincial capital, Port Royal. In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, France formally ceded Acadia to Britain. However, there was disagreement about the provincial boundaries, and some Acadians also resisted British rule. With renewed war imminent in 1744, the leaders of New France formulated plans to retake what the British called Nova Scotia with an assault on the capital, which the British had renamed Annapolis Royal.

Siege of Annapolis Royal

DuringKing George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

, the neutrality of Le Loutre and the Acadians was tested. By the end of the war, most British officials who had been sympathetic toward the Acadians concluded that they and Le Loutre were supportive of the French position. Le Loutre may have been involved in two raids on the British at Annapolis Royal. The first Siege of Fort Anne

The siege of Annapolis Royal (also known as the siege of Fort Anne) in 1744 involved two of four attempts by the French, along with their Acadian and native allies, to regain the capital of Nova Scotia/Acadia, Annapolis Royal, during King George' ...

was made in July 1744 but ended after four days due to the failure of French naval support to arrive.

A second attempt in September was orchestrated by François Dupont Duvivier

Captain François Dupont Duvivier (; 25 April 1705 – 28 May 1776) was an Acadian-born merchant and officer of the French colonial troupes de la marine. He was the wealthiest offer on Ile Royale and led the Raid on Canso and Siege of Annapoli ...

. Without with siege guns and cannon, Duvivier could make little headway. In the late-spring/early summer Nova Scotia Lieutenant-Governor Paul Mascarene

Jean-Paul Mascarene (c. 1684 – 22 January 1760) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator who served as commander of the 40th Regiment of Foot and governor of Nova Scotia from 1740 to 1749. During this period, he led the colony th ...

wrote to Massachusetts governor William Shirley

William Shirley (2 December 1694 – 24 March 1771) was a British Army officer and colonial administrator who served as the governor of the British American colonies of Massachusetts Bay and the Bahamas. He is best known for his role in organi ...

requesting military aid. Gorham's Rangers

Gorham's Rangers was one of the most famous and effective ranger units raised in colonial North America. Formed by John Gorham, the unit served as the prototype for many subsequent ranger forces, including the better known Rogers' Rangers. The ...

arrived in late September to reinforce the garrison. Wampanoag

The Wampanoag , also rendered Wôpanâak, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands based in southeastern Massachusetts and historically parts of eastern Rhode Island,Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. 17 ...

, Nauset

The Nauset people, sometimes referred to as the Cape Cod Indians, were a Native American tribe who lived in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. They lived east of Bass River and lands occupied by their closely-related neighbors, the Wampanoag.

Although the ...

, and Pequawket

The Pequawket (also Pigwacket and many other spelling variants, from Eastern Abenaki

The Abenaki (Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-spea ...

members were offered bounties for Mi'kmaq scalps and prisoners as part of their pay. The Mi'kmaq's withdrew and Duvivier was forced to retreat back to Grand Pré

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

* Grand Mixer DXT, American turntablist

* Grand Puba (born 1966), American rapper

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma

* Grand, Vosges, village and comm ...

in early October. After the two attacks on Annapolis Royal, Massachusetts Governor William Shirley put a bounty on the Passamaquoddy

The Passamaquoddy ( Maliseet-Passamaquoddy: ''Peskotomuhkati'') are a Native American/First Nations people who live in northeastern North America. Their traditional homeland, Peskotomuhkatik'','' straddles the Canadian province of New Brunswick ...

, Mi’kmaq and Maliseet

The Wəlastəkwewiyik, or Maliseet (, also spelled Malecite), are an Algonquian-speaking First Nation of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They are the indigenous people of the Wolastoq ( Saint John River) valley and its tributaries. Their territory ...

.

The following year, Louisburg fell for the first time to a force of New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

ers. After the capture of Louisberg, the British attempted to lure La Loutre to come there for his own safety, but he chose to go to Québec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Government of Canada, Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is ...

to confer with the authorities. They made Le Loutre their liaison with the Mi'kmaq, who were already at war with the British along the frontier. Thus the French government could work with the Mi'kmaq militia in Acadia.

Duc d'Anville Expedition

Yet another attempt Annapolis Royal was organized withJean-Baptiste Nicolas Roch de Ramezay

Jean-Baptiste Nicolas Roch, ''Seigneur de Ramezay'', (4 September 1708, in Montreal, New France – 7 May 1777, in Blaye, France; officer of the marines and colonial administrator for New France during the 18th century. Joining at age 11, as an ...

and the ill-fated Duc d'Anville Expedition in 1746. With Louisbourg captured by the British, Le Loutre became the liaison between the Acadian settlers and French expeditions by land and sea. The authorities directed him to receive the expedition at Baie de Chibouctou (Halifax Harbour

Halifax Harbour is a large natural harbour on the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, Canada, located in the Halifax Regional Municipality. Halifax largely owes its existence to the harbour, being one of the largest and deepest ice-free natural harbo ...

in present-day Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

). Le Loutre was virtually the only person to know the signals to identify the ships of the fleet. He had to coordinate the operations of the naval force with those of the army of Ramezay, sent to retake Acadia by capturing Annapolis Royal early in June 1746. Ramezay and his detachment arrived at Beaubassin

Beaubassin was an important Acadian village and trading centre on the Isthmus of Chignecto in what is now Nova Scotia, Canada. The area was a significant place in the geopolitical struggle between the British and French empires. It was establ ...

(near present-day Amherst, Nova Scotia

Amherst ( ) is a town in northwestern Nova Scotia, Canada, located at the northeast end of the Cumberland Basin, an arm of the Bay of Fundy, and south of the Northumberland Strait. The town sits on a height of land at the eastern boundary of th ...

) in July, when only two frigates

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

of the French squadron had reached Baie de Chibouctou. Without seeking the agreement of the two captains, Le Loutre wrote to Ramezay suggesting an attack be made on Annapolis Royal without the full expedition; but his advice was not acted upon. They waited over two months for the expedition to arrive; slowed by contrary winds and ravaged by disease, the expedition returned home.

After the failed expedition, Le Loutre returned to France. While in France, he made two attempts during the war to return to Acadia. On both occasions he was imprisoned by the English. In 1749, after the war, he finally returned.

Father Le Loutre's War

Le Loutre moved his base of operation in 1749 from Shubenacadie to Pointe-à-Beauséjour on theIsthmus of Chignecto

The Isthmus of Chignecto is an isthmus bordering the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia that connects the Nova Scotia peninsula with North America.

The isthmus separates the waters of Chignecto Bay, a sub-basin of the Bay of Fun ...

. When Le Loutre arrived at Beauséjour, France and England were disputing the ownership of present-day New Brunswick. A year after they established Halifax in 1749, the British built forts in the major Acadian communities: Fort Edward (at Piziquid), Fort Vieux Logis

Fort Vieux Logis (later named Fort Montague) was a small British frontier fort built at present-day Hortonville, Nova Scotia, Canada (formerly part of Grand Pre) in 1749, during Father Le Loutre's War (1749). Ranger John Gorham moved a blockhou ...

at Grand Pré and Fort Lawrence

Fort Lawrence was a British fort built during Father Le Loutre's War and located on the Isthmus of Chignecto (in the modern-day community of Fort Lawrence).

Father Le Loutre's War

Despite the British Conquest of Acadia in 1710, Nova Scotia rema ...

(at Beaubassin

Beaubassin was an important Acadian village and trading centre on the Isthmus of Chignecto in what is now Nova Scotia, Canada. The area was a significant place in the geopolitical struggle between the British and French empires. It was establ ...

). They were also interested in building forts in the various Acadian communities to control the local populations.

Le Loutre wrote to the minister of the Marine, "As we cannot openly oppose the English ventures, I think that we cannot do better than to incite the Mi'kmaq to continue warring on the English; my plan is to persuade the Mi'kmaq to send word to the English that they will not permit new settlements to be made in Acadia. … I shall do my best to make it look to the English as if this plan comes from the Mi'kmaq and that I have no part in it."

Governor General Jacques-Pierre de Taffanel de la Jonquière, Marquis de la Jonquière, wrote in 1749 to his superior in France, "It will be the missionaries who will manage all the negotiation, and direct the movement of the savages, who are in excellent hands, as the Reverend Father Germain and Monsieur l'Abbe Le Loutre are very capable of making the most of them, and using them to the greatest advantage for our interests. They will manage their intrigue in such a way as not to appear in it."

As an official peace existed between France and Britain, Le Loutre led the guerrilla resistance to the British building forts in the Acadian villages, because the French army was unable to fight the British, who possessed the territory. Le Loutre and the French were established at Beauséjour, just opposite Beaubassin. Charles Lawrence first tried to establish control over Beauséjour and then at Beaubassin early in 1750, but his forces were repelled by Le Loutre, the Mi'kmaq, and Acadians. On 23 April, Lawrence was unsuccessful in setting a base at Chignecto because Le Loutre burned the village of Beaubassin, preventing Lawrence from using its supplies to establish a fort.

Defeated at Beaubassin, Lawrence went to Piziquid where he built Fort Edward; he forced the Acadians to destroy their church and replaced it with the British fort. Lawrence eventually returned to the area of Beaubassin to build

As an official peace existed between France and Britain, Le Loutre led the guerrilla resistance to the British building forts in the Acadian villages, because the French army was unable to fight the British, who possessed the territory. Le Loutre and the French were established at Beauséjour, just opposite Beaubassin. Charles Lawrence first tried to establish control over Beauséjour and then at Beaubassin early in 1750, but his forces were repelled by Le Loutre, the Mi'kmaq, and Acadians. On 23 April, Lawrence was unsuccessful in setting a base at Chignecto because Le Loutre burned the village of Beaubassin, preventing Lawrence from using its supplies to establish a fort.

Defeated at Beaubassin, Lawrence went to Piziquid where he built Fort Edward; he forced the Acadians to destroy their church and replaced it with the British fort. Lawrence eventually returned to the area of Beaubassin to build Fort Lawrence

Fort Lawrence was a British fort built during Father Le Loutre's War and located on the Isthmus of Chignecto (in the modern-day community of Fort Lawrence).

Father Le Loutre's War

Despite the British Conquest of Acadia in 1710, Nova Scotia rema ...

. He encountered continued resistance there, with the Mi'kmaq and Acadians dug in before Lawrence's return to defend the remains of the village. Le Loutre was joined by the Acadian militia leader Joseph Broussard

Joseph Broussard (1702–1765), also known as Beausoleil ( en, Beautiful Sun), was a leader of the Acadian people in Acadia; later Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick. Broussard organized a Mi'kmaq and Acadian militias against t ...

. They were eventually overwhelmed by force, and the New Englanders erected Fort Lawrence at Beaubassin.

In the spring of 1751, the French countered by building Fort Beauséjour

Fort Beauséjour (), renamed Fort Cumberland in 1755, is a large, five-bastioned fort on the Isthmus of Chignecto in eastern Canada, a neck of land connecting the present-day province of New Brunswick with that of Nova Scotia. The site was strateg ...

. Le Loutre saved the bell from Notre Dame d'Assumption Church in Beaubassin and put it in the cathedral he had built beside Fort Beauséjour. In 1752 he proposed a plan to the French court to destroy Fort Lawrence and return Beaubassin to the Mi'kmaq and Acadians.

Both New England and New France military officials made allies of the aboriginal tribes in their struggles for control. The aboriginal allies also engaged independently in warfare against the colonists and opposing tribes, without their English or French allies. Often aboriginal allies fought on their own while the imperial powers tried to conceal their involvement in such initiatives, to prevent igniting large-scale warfare between England and France. Le Loutre worked with the Mi'kmaq to harass British settlers and prevent the expansion of British settlements. By the time Cornwallis had arrived in Halifax, there was a long history of conflict between the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of four principal Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet ( ...

(which included the Mi'kmaq) and the British.

Governor Edward Cornwallis

Edward Cornwallis ( – 14 January 1776) was a British career military officer and was a member of the aristocratic Cornwallis family, who reached the rank of Lieutenant General. After Cornwallis fought in Scotland, putting down the Jacobi ...

was informed in August that two vessels were attacked by the Indians at Canso

The Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation (CANSO) is a representative body of companies that provide air traffic control. It represents the interests of Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs). CANSO members are responsible for supporting ov ...

whereby "three English and seven Indians were killed." Council believed the attack had been orchestrated by an Abbe Le Loutre. The Governor offered a reward of £50 for capture of La Loutre dead or alive.

Raid on Dartmouth (1749)

On September 30, 1749 when a Mi'kmaq force from Chignecto raided Major Ezekiel Gilman's sawmill at present-dayDartmouth, Nova Scotia

Dartmouth ( ) is an urban community and former city located in the Halifax Regional Municipality of Nova Scotia, Canada. Dartmouth is located on the eastern shore of Halifax Harbour. Dartmouth has been nicknamed the City of Lakes, after the larg ...

, killing four workers and wounding two. In response, Cornwallis issued a proclamation offering a bounty for the capture or scalps of Mi'kmaw men and for the capture of women and children: "every Indian you shall destroy (upon producing ''his'' Scalp as the Custom is) or every Indian taken, Man, Woman or Child."

In this Cornwallis followed the example set in New England. He set the price at the same rate that the Mi'kmaq received from the French for British scalps. Rangers scoured the area around Halifax looking for Mi'kmaq, but never found any.

Acadian exodus (1750–52)

With the founding of Halifax and the British occupation of Nova Scotia intensifying, Le Loutre led the Acadians who lived in theCobequid

The old name Cobequid was derived from the Mi'kmaq word "Wagobagitk" meaning "the bay runs far up", in reference to the area surrounding the easternmost inlet of the Minas Basin, a body of water called Cobequid Bay.

Cobequid was granted in 1689 to ...

region of mainland Nova Scotia to New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island (PEI; ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is the smallest province in terms of land area and population, but the most densely populated. The island has seve ...

. Cornwallis tried to prevent the Acadians from leaving as the English preferred to retain their substantial economic value in farming. However, deputies of the Acadian communities presented him with a petition to allow them to refuse to take arms against fellow Frenchman or they would leave. Cornwallis strongly refused their request and directed them that if they left, they could not take any belongings, and warned them that if they went to the area north of the Missaguash River The Missaguash River (French: Rivière Missaguash) is a small Canadian river that forms the southern portion of the inter-provincial boundary between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick on the Isthmus of Chignecto. It had historic significance in the 18t ...

they would still be in English territory and still be British subjects.

The Cobequid Acadians wrote to the people in Beaubassin about British soldiers who, "... came furtively during the night to take our pastor irardand our four deputies .... British officerread the orders by which he was authorized to seize all the muskets in our houses, thereby reducing us to the condition of the Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

.... Thus we see ourselves on the brink of destruction, liable to be captured and transported to the English islands and to lose our religion."

Despite Cornwallis' threats, most Acadians in the Cobequid followed Le Loutre. The priest tried to establish new communities, but found it difficult to supply the new settlers, the Mi'qmaq, and the garrisons at Fort Beauséjour and Île Saint-Jean

Isle Saint-Jean was a French colony in North America that existed from 1713 to 1763 on what is today Prince Edward Island.

History

After 1713, France engaged in a reaffirmation of its territory in Acadia. Besides the construction of Louisb ...

(now Prince Edward Island) with food and other necessities. Finding the living conditions deplorable at New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, he made repeated appeals in 1752 for aid from the authorities in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

. He returned to France to seek funds, which he gained in 1753 from the courts, for the purpose of building dykes in Acadia. Protecting low-lying lands from the tides would enable their use as pasture for cattle and development with cultivation for crops, so the Acadians could escape the risk of starvation. Granted additional monies, Le Loutre sailed back to Acadia with other missionaries in 1753.

Battle of Fort Beauséjour (1755)

In 1754 Bishop

In 1754 Bishop Henri-Marie Dubreil de Pontbriand

Henri-Marie Dubreuil de Pontbriand ( c. January 1708 – 8 June 1760), who became the sixth bishop of Roman Catholic diocese of Quebec, was from a titled family and grew up at the Pontbriand Château (now in Ille-et-Vilaine), France.

Biography

He ...

of Quebec appointed Le Loutre vicar-general

A vicar general (previously, archdeacon) is the principal deputy of the bishop of a diocese for the exercise of administrative authority and possesses the title of local ordinary. As vicar of the bishop, the vicar general exercises the bishop's ...

of Acadia. He continued to encourage the Mi'kmaq to harass the British. He directed Acadians from Minas and Port Royal to assist in building a cathedral at Beauséjour. It was an exact replica of the original Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral

Notre Dame, French for "Our Lady", a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, most commonly refers to:

* Notre-Dame de Paris, a cathedral in Paris, France

* University of Notre Dame, a university in Indiana, United States

** Notre Dame Fighting Irish, the ...

. A month after the cathedral was completed, the British attacked. Upon the imminent fall of Fort Beauséjour, Le Loutre burned the cathedral to the ground to prevent its falling into the hands of the British. He had the bell removed and saved. Not only were such cast bells expensive, that particular bell was a symbolic act of hope for rebuilding, as he had brought it from the church at Beaubassin when that village was burned. The defeat was the catalyst for the Deportation of the Acadians

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians (french: Le Grand Dérangement or ), was the forced removal, by the British, of the Acadian peo ...

. The bell is held at the Fort Beauséjour National Historic Site.

Imprisonment, death and legacy

Aware of his risk, Le Loutre escaped to Quebec through the woods. In the late summer, he returned to Louisbourg and sailed for France. His ship was seized by the British in September 1755, and Le Loutre was taken prisoner. After three months in

Aware of his risk, Le Loutre escaped to Quebec through the woods. In the late summer, he returned to Louisbourg and sailed for France. His ship was seized by the British in September 1755, and Le Loutre was taken prisoner. After three months in Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, he was held in Elizabeth Castle

Elizabeth Castle () is a castle and tourist attraction, on a tidal island within the parish of Saint Helier, Jersey. Construction was started in the 16th century when the power of the cannon meant that the existing stronghold at Mont Orgueil w ...

, Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label=Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependencies, Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west F ...

, for eight years, until after the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Kingdom of France, France and Spanish Empire, Spain, with Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal in agree ...

that ended the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

.

After that, he tried to help Acadians deported to France to settle in areas such as Morlaix

Morlaix (; br, Montroulez) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in northwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

Leisure and tourism

The old quarter of the town has winding streets of cobbled stones and overhan ...

, Saint-Malo

Saint-Malo (, , ; Gallo: ; ) is a historic French port in Ille-et-Vilaine, Brittany, on the English Channel coast.

The walled city had a long history of piracy, earning much wealth from local extortion and overseas adventures. In 1944, the Alli ...

, and Poitou

Poitou (, , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical c ...

. Le Loutre died at Nantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabita ...

on 30 September 1772 on a trip to Poitou to show Acadians the land. He was buried the following day at the Church of St. Leonard. Le Loutre willed his worldly possessions to the displaced Acadians.

Historian Micheline Johnson has described him as "the soul of the Acadian resistance," and he enjoyed wide support amongst French-Canadian priest-historians of the 19th and 20th centuries. A street of Gatineau

Gatineau ( ; ) is a city in western Quebec, Canada. It is located on the northern bank of the Ottawa River, immediately across from Ottawa, Ontario. Gatineau is the largest city in the Outaouais administrative region and is part of Canada's N ...

, Quebec, is named in his memory.

See also

*Battle at Chignecto

The Battle at Chignecto happened during Father Le Loutre's War when Charles Lawrence (British Army officer), Charles Lawrence, in command of the 45th Regiment of Foot (Hugh Warburton's regiment) and the 47th Regiment of Foot, 47th Regiment (Pereg ...

*Military history of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia (also known as Mi'kma'ki and Acadia) is a Canadian province located in Canada's Maritimes. The region was initially occupied by Mi'kmaq. The colonial history of Nova Scotia includes the present-day Canadian Maritime provinces and th ...

*Military history of the Acadians

The military history of the Acadians consisted primarily of militias made up of Acadian settlers who participated in wars against the English (the British after 1707) in coordination with the Wabanaki Confederacy (particularly the Mi'kmaw mili ...

References

Sources

;Primary Texts * * ;Secondary sources * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Video - Abbe Le Loutre

BluPete

Daniel Paul Website, Mi'kmaq Account {{DEFAULTSORT:Le Loutre, Jean-Louis 1709 births 1772 deaths 18th-century French military personnel 18th-century French Roman Catholic priests Canadian military personnel from Nova Scotia Military history of New England Military history of the Thirteen Colonies Canadian military personnel from New Brunswick Acadian people Military history of Nova Scotia Canadian Christian religious leaders Military history of Acadia People from Morlaix Sipekneꞌkatik First Nation People of Father Le Loutre's War